Imagine a browser window. Now, imagine you have 43 tabs open.

Three of them are frozen. One is playing music, but you can’t find where it’s coming from. And you—the user—are paralyzed, staring at the cursor, knowing you have a deadline in ten minutes.

This is the visceral reality of ADHD Symptoms. It is not merely a deficit of attention; it is a surplus of cognition that lacks a reliable filtration system.

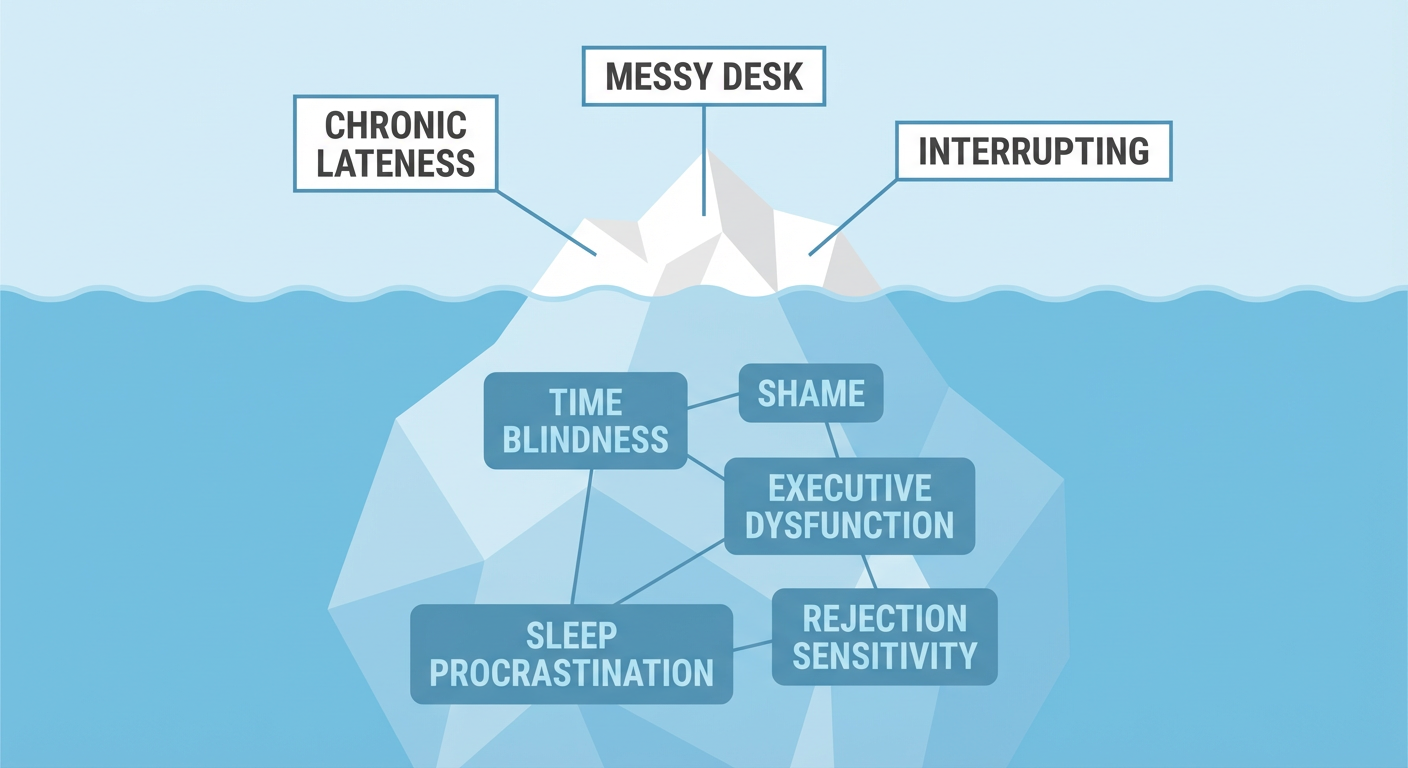

For decades, clinical definitions have focused on what ADHD looks like from the outside—the fidgeting child, the disorganized employee, the "daydreamer." But this external view misses the profound internal architecture of the neurodivergent mind. To truly answer the question, "Do I have ADHD?", we must shift our gaze from behavior to biology, and from pathology to phenomenology.

Therapist’s Note

In my practice, the most exhausting symptom I treat isn’t distraction—it’s masking. Many of you have spent a lifetime building a façade of "normalcy," using anxiety as a fuel source to force your brain into submission. You sit on your hands to stop the fidgeting. You obsessively check lists to hide the memory gaps. By the time you reach my couch, you aren't just unfocused; you are deeply, soul-crushingly tired.

The Evolutionary Lens: Hunters in a Farmer’s World

Before we dissect the symptoms, we must understand the origin. Why would evolution preserve a genetic trait that makes it hard to sit still or finish a spreadsheet?

The answer lies in the "Hunter vs. Farmer" hypothesis.

For the vast majority of human history, we were nomadic. In a high-risk environment, the traits we now label as "disorder" were actually superpowers:

- Distractibility was high alert scanning for predators.

- Impulsivity was rapid decision-making when chasing prey.

- Hyperactivity was the motor drive needed to traverse miles of terrain.

The problem arises not because your brain is broken, but because the context has shifted. We have taken the Hunter’s brain and placed it inside the Farmer’s world—a world of cubicles, routine, slow-growth crops, and sitting still for eight hours a day.

This mismatch creates friction. When you feel restless in a meeting, it isn't a moral failing; it is your biology screaming for a stimulus that the modern office cannot provide.

Anatomy of the Spectrum: Decoding the Symptoms

If you are asking, "How can you tell if you have ADD or ADHD?", you are already touching on a common confusion. The term "ADD" is technically outdated. Since 1987, the medical community has grouped everything under ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder), broken down into three presentations: Inattentive, Hyperactive-Impulsive, and Combined.

But lists of criteria often feel dry. Let's look at the engines driving these behaviors.

1. The Interest-Based Nervous System

Most neurotypical brains have an Importance-Based nervous system. They can see a task is important (e.g., "Do taxes") and mobilize the energy to do it.

The ADHD brain is different. It possesses an Interest-Based nervous system. Importance, rewards, and consequences often fail to activate the brain’s ignition. Instead, you are fueled by four specific elements:

- Interest (Is it fascinating?)

- Challenge (Is it difficult?)

- Novelty (Is it new?)

- Urgency (Is it due right now?)

This explains the paradox of Hyperfocus. You can’t focus on a 10-minute email, yet you can focus on a video game, a coding problem, or a painting for six hours straight. You are not lacking attention; you have an inconsistent regulator for it.

2. The Internal Motor (Hyperactivity)

Hyperactivity is not always running around a classroom. In adults, especially women, this symptom often internalizes.

It manifests as a racing mind that never sleeps. It is the constant need to reorganize, the inability to relax without feeling "unproductive," or the subtle, repetitive movements like skin picking or leg bouncing. It is a feeling of being driven by a motor that has no "off" switch.

3. Emotional Flooding (RSD)

Perhaps the most painful aspect of ADHD is rarely found in the DSM-5: Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD).

Because the ADHD brain has no "brakes" for stimuli, it also struggles to brake for emotion. A minor criticism or a perceived slight can trigger an overwhelming physical wave of emotional pain. This is not "being dramatic"; it is a physiological inability to modulate the intensity of feelings.

Therapist’s Note

I often hear clients describe RSD as an "emotional sunburn." Even a gentle touch—a neutral email from a boss or a partner’s sigh—can feel agonizing. Recognizing this as a biological symptom, rather than a personality flaw, is often the first step toward healing your self-esteem.

The Memory Paradox: "Why Did I Walk Into This Room?"

A frequent secondary question I encounter is: Does ADHD affect memory?

The answer is yes, but specifically your Working Memory.

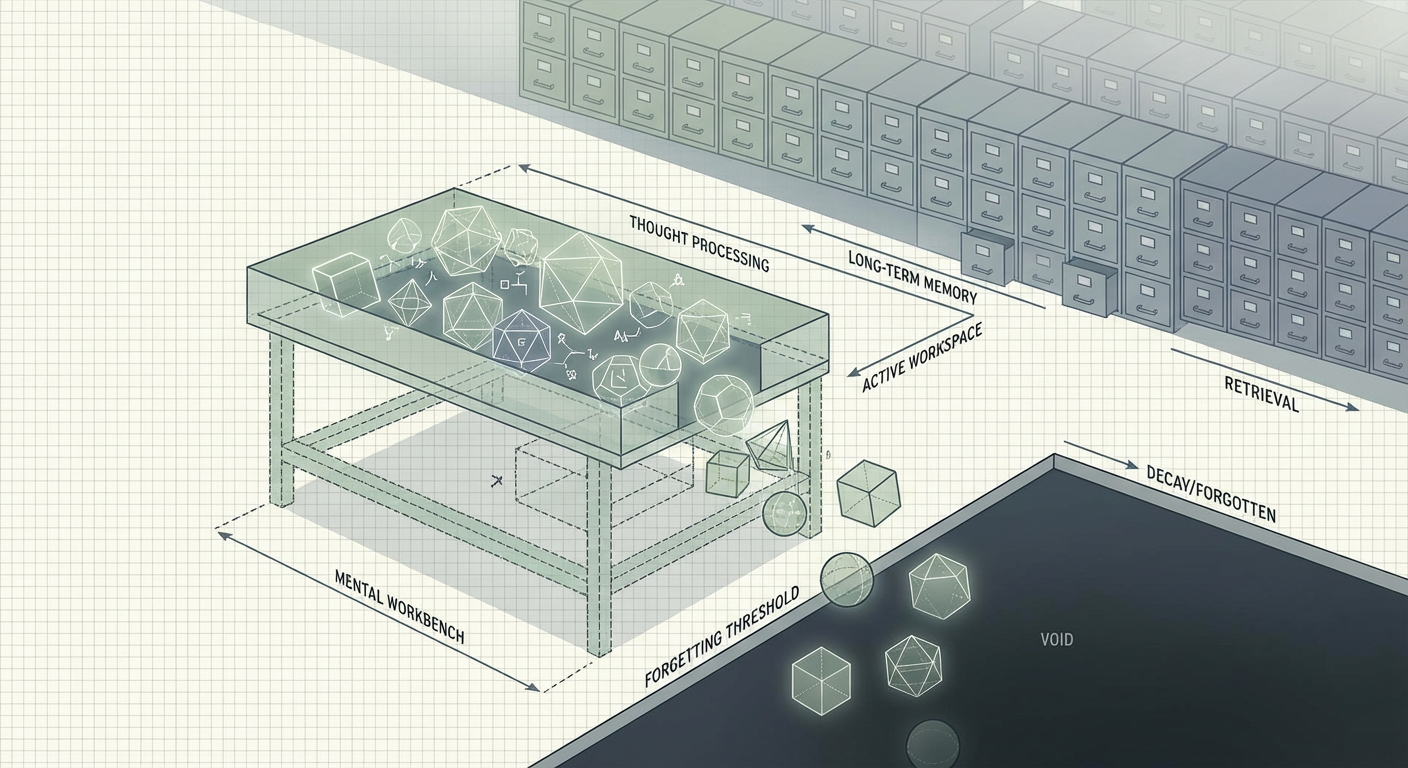

Think of your memory system like a library.

- Long-Term Memory is the stacks. ADHD brains often have incredible long-term vaults, remembering obscure facts from 1999 or the lyrics to every song on an album.

- Working Memory is the librarian’s desk (the "workbench"). This is where you hold information temporarily while you use it.

In an ADHD brain, the workbench is remarkably small and slippery.

When you walk into a room and forget why, it’s because the thought ("Get the scissors") fell off the workbench the moment you saw the pile of laundry ("Visual distraction"). You didn't have a memory failure; you had a capacity failure. This is why you can be brilliant at complex strategy yet struggle to remember to switch the laundry.

Moving from Diagnosis to Design

So, do I have ADHD?

Diagnosis is complex. It requires a professional to rule out anxiety, trauma, or thyroid issues, which can mimic the symptoms. However, self-recognition is a powerful indicator.

If you identify with the Inattentive type (formerly ADD), your struggle is likely internal: drifting, fog, and the "space cadet" label. If you are Combined or Hyperactive, your struggle is often friction with the world: interrupting, impulsivity, and restlessness.

But here lies a deeper truth. A diagnosis is not a life sentence of deficit. It is an operating manual for a different kind of machine.

Therapist’s Note

There is a specific grief that comes with a late diagnosis. You look back at your younger self—the one who was called "lazy" or "careless"—and you want to weep for them. You realize you were playing a game with a controller that was wired differently, trying to win by rules you couldn't read. Allow yourself that grief. It is the precursor to acceptance.

The Unique Wiring

We must be careful not to romanticize ADHD, but we must also refuse to pathologize it entirely. The world needs Farmers to maintain consistency, but it desperately needs Hunters to spot the threat on the horizon, to innovate in chaos, and to hyperfocus on the solutions others give up on.

Your brain is not broken. It is merely specialized for a reality that civilization has temporarily forgotten.

If this resonance feels familiar—if you see yourself in the Hunter, the slippery workbench, or the emotional sunburn—you might want to explore exactly where you sit on this spectrum.